SMEs in Cuba: Inside friendly fire

HAVANA, March 11th Just a year or so ago, the appearance of SMEs was greeted with joy and hope by a great deal of the Cuban population, and also by the government apparatus.The decree law that made its creation possible also settled a decades-old debt and, at the same time, allowed many self-employed workers to materialize their aspirations. It also encouraged many other citizens to start their own businesses and life project.

Its approval, from my perspective, responded more to the urgency of a critical economic and social situation than to the conceptualization of the model itself, even when it opened up space for SMEs as a “complement” to the state sector.

Until January, close to 6,600 new economic actors have been approved, of which almost 6,500 are private SMEs, the state ones stand at around 90; while cooperatives reach just over 60. Around 50% are small businesses and the rest is distributed almost equally between micro and medium-sized enterprises.

With a relatively high territorial concentration, about 40% are based in Havana. Regarding the type of activities, they respond more to a combination of opportunity businesses, access to capital and/or previous experience than to any strategy designed by the decision-makers or that is consistent with the main points that contribute to the country’s development strategy, or with territorial development strategies.

The absence of incentives to induce, encourage, promote, and facilitate the birth of enterprises that respond to these national or local objectives is notable, with the exception of science and technology parks. The reasons for this absence can be varied, from ignorance to deficiencies in public policies that induce their birth where they are most convenient.

They are there. Without a doubt, they have filled a space, have generated employment, and have contributed to increasing and diversifying the dwindling supply of goods and services.

In addition, they have boosted articulations with the state enterprise based on pre-financing their productions, supplying them with raw materials or other inputs that the state enterprise cannot acquire, marketing their products or, thanks to the rent of spaces and underused infrastructure in state enterprises.

This has been the case thanks to their “SME dynamism,” their possibilities of accessing the foreign market, to the fact that they have earned the trust of suppliers because they honor payment commitments on time. And it is not by chance that this is the case.

SMEs can pay from accounts abroad and, above all, they take risks, because they have “learned by doing” and because they are solely responsible for their decisions and do not have to wait for anyone “up there” to say yes or no to them.

SMEs are a more developed form of self-employment, due to the fact that they are a legal entity, which makes it possible for them to import even when they are mediated by a state import-export enterprise; because they have shown that YES YOU CAN and that Cubans are second to no one, because they add to the purpose of prosperity because they have discovered new market niches and relatively novel ways of managing it, in the country’s conditions.

Because of all this, perhaps they have concentrated on them not only the fire from the enemy side but also that other that, as former Ecuadoran President Rafael Correa stated, is even more harmful: friendly fire.

A year and a half after their birth it would seem that their success may be their doom. As on other occasions, prejudices have been gaining ground.

Too many SMEs versus a number of state-owned enterprises that do not exceed 2,000, was perhaps one of the first bullets from the friendly fire as if the quantity was decisive and not quality, and as if almost sixty years without small and medium-sized private enterprises and gaps never resolved by state enterprises in both goods and services will hardly count in this story.

A part of these SMEs has occupied those spaces that the state enterprises could not or were prevented from filling or were filled with many inefficiencies and deficiencies. They were opportunities never seized.

It is likely that thousands of other opportunities remain, which at the time were not attended to, waiting for new SMEs. And surely new needs/opportunities will be born.

The best thing would be for state enterprises to be able to compete in speed of reaction with SMEs or to be proactive enough to devise articulations with the new forms of non-state management that would allow them to improve their processes and increase their efficiency.

When this happens, it is due more to the exceptionality of some state entrepreneurs than because the “rules of the game” encourage those decisions to be made.

Many opportunities still do not turn into good businesses, because those “rules of the game” favor more repeating decisions such as “dog in the manger” — neither eat nor let eat —, something deeply rooted in our leadership culture, something that does not seem to be the most suitable for the aspirations of revitalizing an economy that has been stagnant for several years.

The corporate purpose has been another of the targets of “friendly fire.” It is “too wide-ranging,” it has been said, and that allows them to do anything. This gives them “advantages over the state enterprise,” it has been stated.

So, let’s force the new ones that are created to reduce that corporate purpose to a certain number of activities that are directly related to their main activity.

What is surprising is that state-owned enterprises, even before the first SME was officially born, already enjoyed the same power and can, at least in theory, expand their corporate purpose as much as the business opportunities they demand.

If it is a matter of all the actors operating on a “level playing field,” why are SMEs restricted? Why have the state enterprises that accessed this advantage before the SMEs not taken advantage of them? Who does it hurt that SMEs have a wide-ranging corporate purpose?

Who benefits from this “administrative or political decision” to coerce their rights? How is it possible then that administratively it is decided to constrain something that the legislation itself allows?

Is it that restricting the corporate purpose of SMEs has any direct relationship with the improvement of the state enterprise or with the increase in GDP? Or with the improvement of global productivity? Or with the systemic increase in efficiency in the use of resources?

Or with a better allocation of the people’s resources in investments that can be recovered in the scheduled time? Or with the increase in food production and the reduction of its prices?

Another of the projectiles that are used against SMEs is that there is a disconnection between the activities they carry out and the needs of the territories.

It is certainly so and there is evidence to confirm it. However, it is the manifestation of the phenomenon. The causes are not only that they respond to the individual interest of their owners, but also in the limitations of local authorities to induce, motivate, and promote the emergence of other small enterprises in those activities that best suit the territories and at the same time in the few possibilities/resources/instruments that these local governments have in their hands to achieve something like this.

From the fiscal field (taxes, tax exemptions, etc.) the territories can do little since our fiscal policy is highly centralized and essentially consists in collecting.

It is true that they could provide them with premises and even idle land, but a great deal of the premises do not belong to the government, but to the national ministries and enterprises; and on idle land, the faculties rest with the Ministry of Agriculture and its territorial delegations.

But it is also true that they have in their hands the funds for local development, through them, there could be a possibility of incentives, in the same way, that “facilitating” the concretion of these new businesses could also be a resource to encourage and induce the creation of SMEs wherever the territory needs.

That SMEs have “diverted remittances that were previously appropriated by state enterprises” is part of the friendly fire arguments.

The truth is that today we do not have data on the number of annual remittances that Cuba receives. In fact, that data has never been public. Beyond the reports published by Western Union, the rest has been estimated.

These estimates all agree that at their best time, remittances oscillated between 2.5 billion and 3.5 billion. It is also true that basically, they went to state enterprises.

It happens that reality changed. Remittances were affected by the difficulties imposed by Trump’s measures. We had the pandemic.

The shortage of supplies in stores selling in freely convertible currency, as well as the difficulties in using plastic money, together with the expansion of online sales platforms and the massive exodus of some 300,000 Cubans in just over a year, have drastically changed the scenario.

It would be necessary to add the passivity/slowness to implement programs that encourage the sending of remittances to destinations of interest for those who receive remittances — funds for the construction of houses or to be used as microcredits, for example.

It is convenient to remember that the sending of remittances for a long time had as its fundamental purpose the purchase of consumer goods and today a part of that consumption is satisfied by the offer of the new actors, given the ineffectiveness of the stores in freely convertible currency.

Friendly fire has also focused on the relationship between inflation and SMEs. It is true that there are those who profit from the opportunity offered by an economy that for years has suffered from the insufficient supply, but confusing causes with consequences is not good.

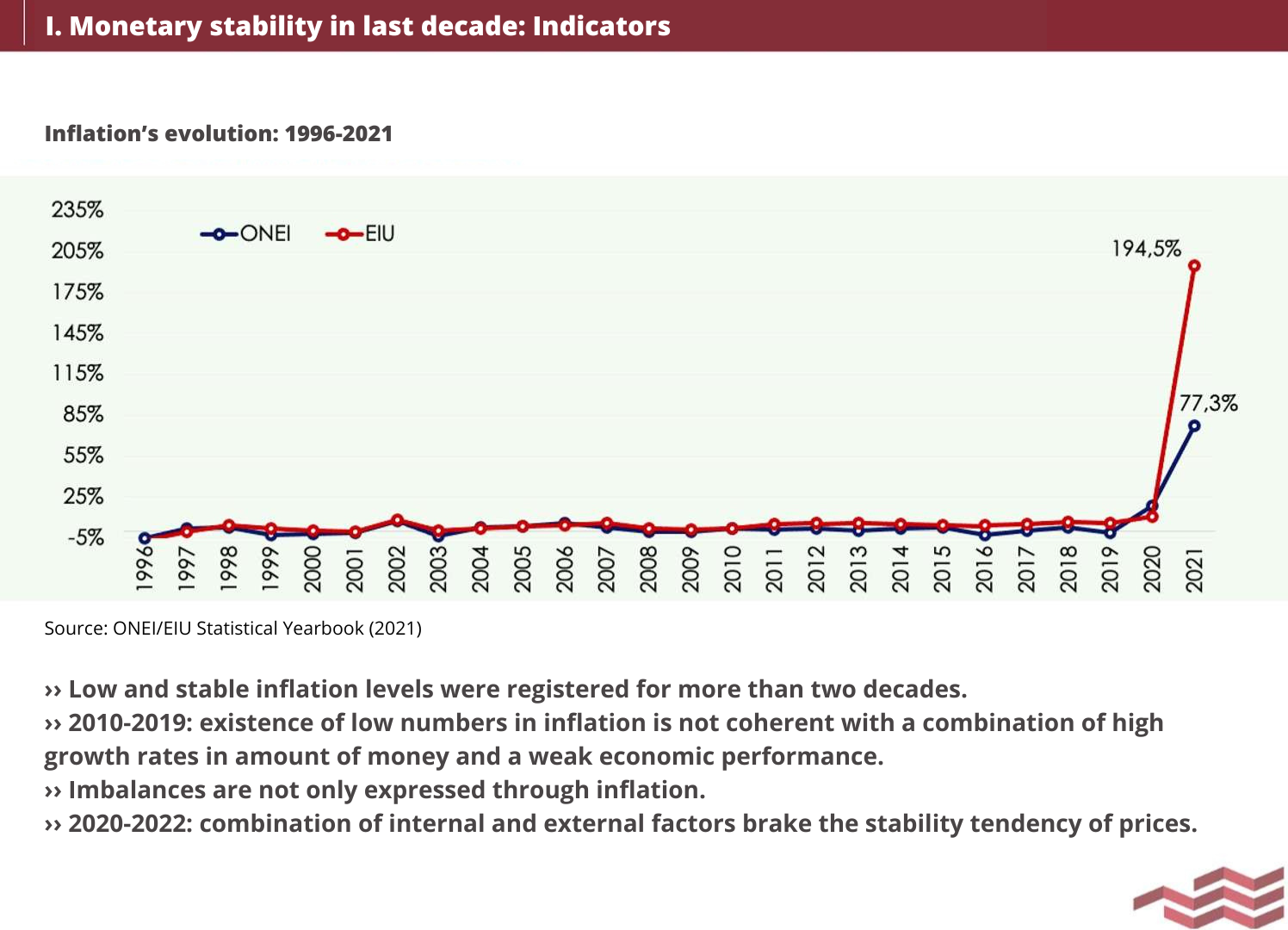

The first SMEs emerged in October 2021. The price behavior data shows the following:

A year before the emergence of SMEs, prices already showed a highly inflationary behavior as a result of external factors such as the increase in international prices of goods and services, especially freight.

Also due to internal factors, as many specialists and the authorities themselves have recognized: a deep supply shock, the increase in money in circulation mainly due to the issuance of money to cover a high fiscal deficit, the almost null success of the Reorganization Task and the effect of the devaluation of the official exchange rate, the reduction in the supply of dollars and, consequently, the rise in the exchange rate together with the creation of an informal currency market and the expectations of the population.

However, we can ask the question that naturally arises: if SMEs and, especially, private online sales platforms and retailers disappear tomorrow, would inflation decrease or disappear?

That social differentiation has grown in Cuba, and, with it, inequality is indisputable and is part of the arsenal from which friendly fire is nourished. That non-state actors have made it more evident is also not in dispute.

However, the growth of inequalities is not a phenomenon that occurred after the approval and emergence of new actors. It also dates back several years.

There is no public data on the Gini Index in Cuba in recent years, but it is good to remember that already at the beginning of this century and under the personal direction of Fidel, a training program for social workers was launched due to the evidence of serious inequalities that have deepened over the years.

More than 1.8 million retirees and pensioners (16% of the total population of the country) live in Cuba today. The State budget tries to support these people, but the average pension (retirees, disability, and death) is around 2,000 CUPs (below the minimum wage, which in 2022 was 2,100 CUPs).

That pension, like the minimum wage, is barely enough to obtain that basic food basket of the “ration book”; and it is far from the income necessary to complement it.

The SMEs were born ten months after the Reorganization Task, which was the one that turned the income of these pensioners into salt and water, despite the increases and, as I explained, a year before inflation significantly reduced purchasing power of those pensions.

It should also be said that SMEs also contribute to social security, both workers and partners.

So let’s go back to the same question: if SMEs did not exist, would the situation of our retirees and pensioners, and families at risk improve? Would the situation of the 367,887 people who receive 1,362 CUP per month improve?

Perhaps a good argument in favor of a positive answer would be that, if SMEs did not exist, the wealth that they concentrate could be better distributed, it would only be necessary to assume that someone had produced it before. Who?

A good friend versed in the issues of the influence of institutions in the Cuban economy told me some time ago that the best way to stop the dynamics of SMEs is to create the Ministry of New Forms of Non-State Management and arm Higher Organizations of Business Management (OSDEs) by type of main activity. Without a doubt, it could be the most powerful projectile from friendly fire.

First published by Oncuba